ELLIS JACOBSON

The Birth of an Artist

Part 1 1925 - 1947

Carme Castells - translated by David Magil

October 2004

On more than one occasion we will

read references to the long career of an Ellis Jacobson who exhibited what he learned previously, either artistically or creatively, in every one of his works. The path that Ellis Jacobson travelled speaks of personal growth, of unrewarding jobs to earn his keep, of an evident thirst for knowledge in long reading sessions, and of periods of deprivation in

the name of art and of his true creative vocation.

Material things are the expression of the paths travelled by the soul. Because of this, we cannot begin this approach to Ellis in media res. We have

to start from the beginning. Go back along the path to the dry cold or the warm sun that prevailed on December 16th, 1925 in San Diego (in southern California, near the US border with Mexico), when the artist poked his head out into the world and decided that yes, he would stay.

1925, America is at the height of the "roaring 20's". It was precisely this year that saw the culmination of the construction of the San Diego Museum of Arts, which would open its doors in February of 1926. The city also opened its fun fair, the Giant Dipper, with an enormous roller coaster and the largest Olympic pool in all

California, The Plunge, was inaugurated. A time of development for San Diego, a city of nearly 100,000 inhabitants.

The artist was born into a "normal, middle-class family, like so many others ." That same middle class that struggles day in and day out to get their business off the ground or keep the job that ensures the family's sustenance. In the Jacobsons' case it was a neon sign and light manufacturing and installation company, so

that Ellis' childhood and youth was to develop in close proximity to neon signs, often with innovative designs. Nevertheless, he was responsible for his own artistic stimulation. "Anything like music, literature, art... I

learned on my own initiative. My family didn't understand me, although they did always support me."

Ellis was a restless child, but not a difficult one. A good boy, or at least that is what we deduce from the artist's words when he delves into the past in search of selected memories. From among them he rescues "the only prank I played in my life": when he was eight, he set fire to a deserted truck on a building site near his home. "The fire brigade had to come out my father told me off, but he really wasn't very strict. I caused one hell of a fuss'' he explains. Pranks aside, the story of Ellis' childhood is packed with creativity: with small initiatives, proof of the preoccupations of an imaginative youngster.

The Jacobsons' garage was the scene of many of these first artistic steps. The first was the creation of a newspaper, "albeit just the first issue. It was a complete failure." He also organised a fair, with different attractions such as balloons with darts to pop them with. "That failed, too." Ellsi father Isidore "Ike" Jacobson had a collection of 16mm films. Ellis used them to set up a cinema in the garage. "I was 14. My father had films about aeroplanes, and that was enough for me. I put the projector in place, set out some chairs and put up a very large sign on the door to advertise my movie house. Then I went outside and started shouting like the paper boys. They used to say Extra! Extra!, so I shouted War! War! The Second World War had just broken out. The grown-ups looked at me in amazement - I guess they were wondering what a kid of my age could know about the war." Needless to say that this initiative was not as successful as the young man in question hoped, but nevertheless it was an early manifestation of his preoccupation with interpreting reality in a creative fashion.

Ellis, 1933

Ellis and his Brother Merrill, 1938

This adventure of creating a home cinema is not an isolated event. Ellis remembers that "at the age of 10 my dream was to become a film director. Of course in those days there weren't the facilities there are now, it wasn't as easy to get ahold of a camera as it is now. This dream drove him to take long walks in the area surrounding his house looking for locations where he could film. "I wanted to make a film about nature with real backgrounds, not the artificial sets of Hollywood". When he was 17 he joined a film course. "I was always a very bad student, I just wasn't interested. But I remember those classes as the most enjoyable of my school years." Ellis clearly places his memory of the course in the historical context of the battle of Stalingrad and the retreat of Hitler's army in Russia,

in January of 1943: "the teacher interrupted the class to inform us that Stalin had defeated the nazis. Good old Stalin, back then he was the good guy...."'

But of all his creative preoccupations, the one which was to absorb Ellis most frequently was that of devouring comics. His favourites were Tarzan, Prince Valiant and above all, the incombustible Flash Gordon. "Doubtless my passion for movies must have influenced the way I look at things and at the world in general. But it isn't something that came before painting. "When I started to take interest in movies I had already been drawing for years.''. He

drew adventure and Mickey style comics trying to capture what he had learned from his devotion to the comic strips. "I learned a lot from them: about composition, and anatomy. I read them, but first and foremost I used to analyse them, and in this way I began to understand who was doing good wrok and who wasn't." His predilection for Flash Gordon refers specially to the first works that Alex Raymond created using this character. "First of all he had a 'heroic' sense of action and distortion of the figures. Raymond is still copied today.

The reference to Flash Gordon is compulsory when reviewing the influences that converged in Ellis' training, because the traces of his vocation for comics and caricatures can be seen quite clearly in his later work, especially in his figurative portraits. And in parallel, Raymond's work was also an icon for Ellis' personal growth "It contained a lot of sexuality for those days. Flash's girlfriend, Dale, didn't wear much in the way of clothes" Ellis was a normal, curious teenager "I insisted on going with my mother when she went to the fish mongers, and it was because there was a ceramic mural on the wall of some mermaids. This was my first encounter with the naked body of a woman." At the age of fourteen Ellis started workign on jobs at his father's neon factory. To start with, he had to do the cleaning on Saturdays. Then more specific jobs were assigned to him. "I didn't like working there, but I learned something about communication. Now whenever I go somewhere like an airport or a shopping centre I can't help noticing if the signs are any good, if they are effective or not, if they have been hung badly, etc. I learned that it is not difficult to communicate if you know how to do it." Standing out from the jobs Ellis did was the preparation of an illustration of a pirate for a large sign. This was the artist's first contact with advertising art: "I painted it with a mixture of oils and latex paint, this was partly my initiation into illustration. Between the ages of 14 and 16, He was to paint many more." Apart from this, he was not at all interested in taking over for his father in the neon factory (his brother, Merill, a far better businessman, became a partner in the business): the only thing he was interested in there was painting. Or rather: the only thing he was interested in was painting, period.

His academic education in early childhood was marked by a desire to draw in a free manner. "In the schools there really were no art classes,

I received poor grades because I didn't want to design Christmas and valentine cards." His love of comics, of caricatures, of comic strips in newspapers, jelled in the form of a vocation for portraits which absorbed Ellis with intensity in this early period of his artistic career. Thus portraits and caricatures constitute the basis th rough whi ch the artist trained his strokes, channelling his creative drive. With regard to caricatures, he says, "When you do a caricature you have to find the real person. When you look at Rembrandt you realise that his genius is out of this world. His composition, his use of black and white, are brilliant. But he doesn't just capture the physical side, he also captures 'something else'. And you can't buy that something else in a bargain store, you have to feel it to capture it." Ellis searched for souls in portraits of people around him, which he drew to earn a few cents, and in caricatures he created almost impulsively from everything that moved around him. And then in 1944, his surroundings changed entirely: like so many other young men in the America of the '40s, he was called up to take part in the Second World War.

Sketch, 1938

Ellis with sister Audrey and brother Merrill, 1941

San Diego Union, Sketch, 1937

San Diego, 1940

Caricatures on San Clemente Island

Ellis was summoned to Los Angeles, on D-day, at H hour to an old cinema which had recently closed down. The men had been separated into two lines: one for infantry, another for the navy. Ellis was put in the navy line, he was posted to the Pacific, however San Clemente Island, in it was to San Clemente Island, just a few miles off the coast of Los Angeles. he was posted there, from 1944 to 1946, he had no contact whatsoever with the misery. or the pai n, or the horror of war. "My contact came later, when I started to see images of what had happened, i mages of the holocaust. I can not erase the face of a woman after a bombardment, a woman who had just dressed herself up and died suddenly, from my memory." His Jewish ancestry also meant he was connected to the conflict in other ways, "I remember my grandmother received letters from Jewish family in Poland and Czechoslovakia, and was extremely worried, and I remember when the letter stopped coming, they all stopped"

Nevertheless, his memories of those years of service in the navy were totally free of any drama. Quite the contrary, Ellis remembers with irony the favour he did his country from the communications post he was sent to. "I had to transmit and intercept information in Morse code. The truth is I wasn't very good at it. Once we intercepted Japanese propaganda. They said they had shot down some American planes, but it wasn't true, it was just propaganda "That was exciting." Ellis paid little attention to the war and battles, even though he was in the Navy he was removed from the action, and in a real sense removed from the American mainland. This isolation gave him many hours a day to draw and practice his cartoons. He felt guilty for how good he had it compared to the men fighting on Pacific islands against the Japanese. His Pacifc island expereince was so different and he was acutely aware that it had been pure luck that landed him on San Clemente, it could just as easily have been Iwo Jima, Guam or Saipan.

USN, 1944

USN Radar Station, San Clemete Island, 1945

Sketch, 1945

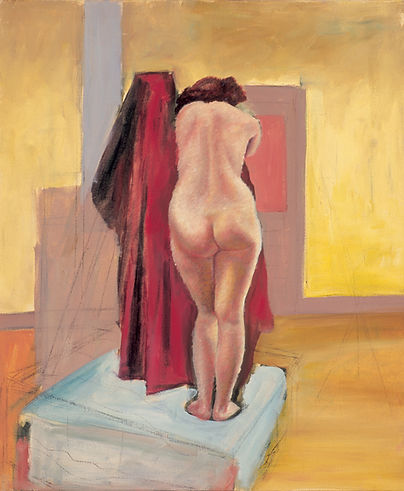

Ellis' academic training, after the interval on San Clemente Island, started at the San Diego School of Arts, in La Jolla, California. "I knew nothing of art. I just drew butts and more butts, I wasn't doing anything special. I had no references to go beyond that, but without knowing what else there was in art, I knew I didn't want to just do figure painting and life drawings." A teacher arrived who was to change everything: Fred Hocks "My first contact with non-figurative art was in San Diego, in the art school, through Fred Hocks. Hocks had started with figuration, but later evolved towards abstract expressionism. Hocks threw open the door of an art language Ellis was not familiar with, but one he sensed: abstraction. Hocks stimulated Ellis creativity and taught him to dispense with all the academic ties that were oppressing him. "One day, Hocks set up an exhibition of his own works in the hall of the school, as though it were a gallery. I remember the moment when I arrived at the school as if it were yesterday. I opened the door and ... Wow!!! It was more, much more than a thunderbolt, 125 billion volts slapped into me. Wham! There were a dozen water colours or more, abstract ones. That changed my life in a flash. Immediately I

said to myself: 'this is where I'm going."' "I have always continued with figurative art, but that was what changed me. Everyone has their story, and their key moments. Like their first poetry book, their first art book. It's nothinng extraordinary. Everyone who is devoted to creation passes through these moments of revelation."

Ellis then moved to Los Angeles, to study at the Chouinard Art Institute. "That is where I really learned to draw." To draw, and many other things besides. And the key, once again, lies in another name: Donald Graham, the second of the teachers who had the most influence on Jacobson. Graham had set up a drawing school. When Walt Disney started making his animated films he needed a larger group of cartoonists. He met Donald and put him in charge of training artists. Ellis was reticent about "the art that was taught in art school". Even Graham's school "taught art, not creativity." But the result was different: "Don taught us many things. The first day of class, I was convinced I was the best in the class, even though there were a lot of students. That same day Don said to me, 'I like what you do. You draw really well, but you have to forget everything you know, because you don't know.' With Don I learned that you can't be arrogant if you want to learn. I learned to draw using both my head and my subconscious with him."

1948

1948

1950

But it was not enough for Ellis to discover these geniuses through Hock's eyes. "He was a great guy, but he had an enormous ego, for him'; the real geniuseswe Michaelangelo and Picasso and himself. And it is true he was good, very good. I think if he had been in Paris 20 years earlier he would have been one of the great artists. He was always affections with me but he never recognised me as a painter.

Now he had to travel in order to experience some of what Hocks had taught him. Ellis wanted to know who Michelangelo was. See the Sistine chapel. Look for·the nooks and crannies where Cezanne used to lose himself. He still did not know who Picasso was, but he was to find out soon enough. He would soon encounter the great portraits painters of Europe in the great museums of Paris and Rome. But for now he had to paint portraits to to amke enough to fund his dreams. The memory of these activity arouses interesting thoughts in Ellis today. "When someone asks you to paint a portrait, the client always criticises the details. What they really want is a photograph. A photograph, but one which has the added value of the human face inherent in the perfect reproduction of reality, without resorting to technology. The client does not want interpretation, he wants an exact copy. Or worse still, an exact copy of imagined reality, of the image one does not have, but dreams of having". "This is something which is intensified even more when the client is a woman, Ellis explains, "There is a great deal of difference between drawing a caricature of a man or drawing one of a woman. Men are accustomed to seeing themselves with more frankness. If a man has a hooked, prominent nose, you have to draw it. But if a woman has one... you have to be very careful. Women don't like to see their defects. You have to try and portray them as harmonious, beautiful, elegant....'' In spite of the unrewarding nature of the work, the portraits and cariacatures that Ellis drew during this period enabled him to save up enough money and so, one day in 1952 he landed in Paris. "It was a different world.''